Uncle Ike’s Pot Shop sits on the corner of 23rd Avenue East and East Union Street in Seattle’s Central District, just a mile from downtown. The neighborhood — once Jewish, then Japanese — became largely Black in 1960s. During the crack epidemic of the ‘80s, the block was one of the most dangerous in Seattle, and many Black families with the resources to do so moved elsewhere. Local journalists still tend to refer to the intersection with terms like “gritty,” “long-troubled,” and “infamous,” but the area has been steadily gentrifying since the 1990s.

Ian Karl Eisenberg, who founded Uncle Ike’s, has been buying property on the block since 2009. Besides the pot shop, he owns a restaurant, a car wash, and buildings that house offices and a bar and lounge. Some of these buildings were abandoned when he bought them. Eisenberg has wagered millions of dollars on the block, but until he opened Uncle Ike’s in 2014, he was afraid he’d made a bad bet. The store is now the highest-grossing cannabis retailer in the state.

The area has prospered economically and crime rates have fallen, but gentrification has proven divisive. Uncle Ike’s has provoked the ire of several local groups. On Wednesday, amid the city’s 4/20 festivities, protesters blocked the intersection in front of Uncle Ike’s, shouting “No justice, no weed” and “Uncle Ike’s has got to go.”

The protesters have several objections to Uncle Ike’s. The most immediate is the pot shop’s proximity to the Mount Calvary Christian Center church and the church’s Joshua Generation Teen Center. Washington state law dictates that cannabis businesses can’t be too close to places where children congregate, such as youth centers, schools, and playgrounds. Churches aren’t included on this list, and, in response to a lawsuit filed in 2014 by the church, state lawyers argued that the teen center doesn’t qualify as a youth center, either. According to lawyers who spoke with Pastor Reggie Witherspoon Sr., the teen center is open just ten days a month, and almost exclusively for religious activities. The church has filed two lawsuits against Uncle Ike’s, both of which have been ruled in the store’s favor. NAACP official Sheley Secrest has objected to these decisions, arguing that the law was clearly written to protect children: “Whoever says it’s not a legitimate teen center is ducking, and we want the law enforced.”

Besides its proximity to the church and youth center, some protesters bristle at what they see as a cruelly ironic development in cannabis history. The intersection at 23rd and Union has been the site of many drug arrests. Pastor Witherspoon reportedly told Seattle Mayor Ed Murray that if Uncle Ike’s is allowed to retain its location, then the mayor “needs to let all the brothers and sisters go who are incarcerated for marijuana.” Hip-hop artist Draze takes a similar line in his new song Irony on 23rd, which he performed at the protests Wednesday.

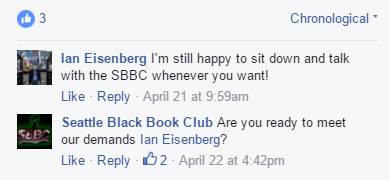

The Seattle Black Book Club (SBBC), a Black-led community organizing group whose members strive for “Black liberation,” has taken an even harder line toward Eisenberg. Their Facebook page features an essay titled “Take A Hike Uncle Ike! Gentrification Stops Here!” In objecting to the store, the article cites neocolonialism and systemic racism, and features a list of demands for Eisenberg. The first is that he give “54 percent of his real estate holdings to the community for the purpose of community-controlled low-income housing.”

The anger directed at Uncle Ike’s reflects wider discontent among marginalized communities across the country with the way cannabis legalization has played out. This anger, broadly speaking, is justified: the legal history of cannabis speaks volumes about race and class in the United States. A 2013 ACLU study found that police arrest Black people nearly four times as often as they arrest white people. A former Nixon official recently admitted that the War on Drugs, which led to the arrest on marijuana possession charges of more than 600,000 people in 2014 alone, was created to disrupt the Black population.

In an interview on Democracy Now last Thursday, Wanda James, CEO of Simply Pure, a Denver-based cannabis dispensary, connected the disproportionate rates at which Black Americans are arrested for cannabis possession to the private prison industry and its need for “slave labor”:

“If you can name a corporation right now, they are profiting off of labor, enslaved labor. . . . To fill those spots, they need to be able to put bodies into those prison systems. And those bodies right now are being collected on the streets of America through cannabis arrest. We’re seeing last year alone that 701,000 people were arrested for simple possession of cannabis.”

Some have argued that the scarcity of Black-owned cannabis businesses in states that have legalized the drug reflects the disproportionate rate at which Blacks are arrested for cannabis possession. In an interview with Tom McKay in MERRY JANE, Kris Krane, the former director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, said that “it’s obvious from attending a marijuana business conference that the industry is heavily white and heavily male.”

In states that have legalized cannabis, the motivating factors for this disparity are knotty. As in any industry, having a prior drug conviction can make it more difficult to enter the cannabis business. And although some states, such as Oregon, have moved to expunge prior marijuana convictions, this is not the norm. That said, a prior cannabis conviction doesn’t necessarily bar you from entering the industry.

Regulatory systems differ among states that have legalized cannabis. Washington State, like Oregon, regulates the drug as it does alcohol — it uses a point system to determine whether people with criminal records are eligible for a license to sell alcohol or cannabis. The cutoff is eight or more points. A felony earns you 12 points, which stay on your record for ten years; misdemeanors get you four points apiece for four years. In a state with more draconian enforcement policies, these points would have greater effect; in Washington, cannabis enforcement has officially been the police force’s lowest priority since 2003. Voters approved full marijuana legalization in 2012, so theoretically only people with felony cannabis convictions should be barred from obtaining a cannabis license. (Though the wording of the law is sometimes startlingly vague—Oregon can deny you a license if you are not “of good repute and moral character.”)

And the state has no say over whom pot shop owners can hire. In a phone interview with Ganjapreneur, Eisenberg said that Uncle Ike’s looks to hire people with knowledge of the product — and that “if they live in the neighborhood, that’s like ten gold stars on the resume.” Of course, Eisenberg is thinking about Seattle’s notorious traffic and Ike’s bottom line: “It’s not because I’m trying to be a do-gooder anti-gentrification person — it’s because I want people to show up to work on time.”

In states that have legalized cannabis, the most salient barrier to entry in the cannabis industry is economic. State licensure rules set up by state governments make it difficult to enter the industry without deep pockets. In the MERRY JANE interview, Krane cited fees of “between $200,000 and $1.5 million … and demonstrated capital just to apply.” Less-than-affluent people “have no capital to start a business, they are unlikely to be hired by shopkeepers, there is no small business administration program that is actively helping them start a new venture,” said Columbia University sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh. “When the government put the regs in place, they made it impossible for most low-income people to ever enter the economy.” Jonathan Caulkins, drug policy expert at Carnegie Mellon University, noted that white people have been able to move from the black market to the legal cannabis industry more easily because of where they were in the black market: “In the short run, it’s mostly people coming over from producing medical and high-end black market, which disproportionately served a more educated and more affluent market and was disproportionately white.”

Because people of color are more likely to confront these economic barriers, the way states have regulated legal cannabis has engendered a cruelly ironic development in the racial history of the drug’s legal status. In an interview with The Seattle Times in February, Eisenberg acknowledged as much, asking “How do you set up a system” in which those communities that have been hurt by decades of racist policies and policing “can benefit in the same ratio they were disproportionately harmed, especially in a heavily regulated industry?” Eisenberg says he donates to the ACLU’s Mass Incarceration project, and that he is involved with the local YMCA and a nearby high school’s teen center. But he isn’t about to accede to the demands of groups like the Seattle Black Book Club, whose goals he says are unclear to him. Eisenberg has offered to meet with the group’s members, but they appear unwilling to negotiate:

When I asked him about Washington State’s drug laws, he said that “all the drug laws are bullshit, and if somebody has a bullshit drug conviction I wouldn’t care if they’re in the legal market.” He also said that the state should expunge the records of people who have been charged with simple cannabis possession charges, and that “in terms of getting a lot of people actually released, I think you ask for baby steps.”

Regardless of what Eisenberg says, groups like the SBBC will likely continue to harbor resentment over the presence of pot shops like Uncle Ike’s in neighborhoods that were hit hard by marijuana prohibition. It’s important that cannabis industry entrepreneurs and activists pay attention to stories like these. Who benefits most from cannabis legalization? We may all be happy about burning down prohibition, but creating truly egalitarian regulations isn’t that simple — and so far, we’ve failed.

Legalizing cannabis is a good thing. But if industry rules cement the economic effects of racist policies, then we’re only reinforcing the status quo. As states continue to scrap old marijuana laws, those on the side of legalization should think critically about who stands to profit from proposed regulatory systems. A movement as progressive as the push for cannabis legalization must do more to bring about rules that might level what has long been an uneven field of play.

Get daily cannabis business news updates. Subscribe

End