The Renegade Chef is the most health-minded badass you’ll ever see in the kitchen.

Chef Jason Snyder is reemerging on the California cannabis scene as the go-to high-end cannabis chef.

He’s been schooled by the best and graduated from the world-famous E.N.S.P pastry school in France. Now, it’s his turn to turn his passion into a delectable reality.

“I’m still doing my Michelin quality food,” Snyder said, “but also incorporating the cannabis part to it on a medical level.”

Working under chefs for the past seven years was difficult, he said, especially spending long hours at restaurants, away from family and friends. Today, he knows it was all worth it because he’s doing what he believes in — healthy, cannabis-infused alternatives to the often fatty, sugary foods in America.

A true renegade

Formerly The Crafted Chef, 2017 is going to be his breakthrough year with his own company, The Renegade Chef Co.

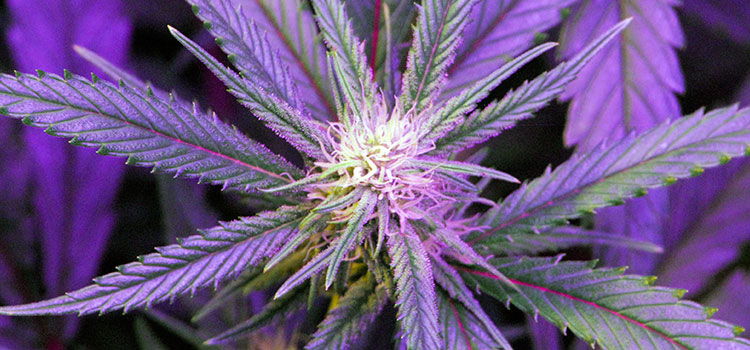

Chef Snyder is preparing for his own edible oils using top-quality flower. He’s experimenting with infused grapeseed and coconut oils. As a specialist in handmade, artisanal, top quality food, he’s experimenting with infused grapeseed and coconut oils. Think cold pressed juices, granolas, and goji berries — not gummies and cookies.

Vegan and super foods with the theme of eating healthy — it’s part of a food movement to transition Americans away from pills. “I’m trying to make nothing in a pill form because it can be a drug abuse trigger for some people,” Snyder said.

The Renegade Chef is working to penetrate the edible market in a thoughtful, professional, and responsible way. “I’m working with CBDs too, I’m developing a line of patient-friendly food for those who have to medicate daily – it’s a better option than brownies all day,” he said.

It’s also tastier than medicating with cannabis oil, which can leave an arguably bad taste.

“There’s more to medical edibles than you see right now on the shelves, I’m working on ice creams and sorbets for those who can’t eat solids,” he said.

The cost of business

It’s not about the money or fame for the renegade — it’s a mission.

“I’ve discovered my true purpose, and how I want to display it,” said Snyder.

Aside from developing his cabinet of cannabis edibles, he caters private parties in adult-use states like California. He prides himself on his safety-conscious private events, where alcohol and cannabis are never mixed and the event includes a ride home to ensure a safe and enjoyable experience for everyone.

The chef believes he’s onto something bigger than just a celebrity brand, and he’s willing to put in the hours because, as he said, “when you believe in what you do, then it’s not work.”

Caution for aspiring cannabis chefs

The chef’s advice is simple: “Make sure your food speaks for its taste, then infuse it.”

Also, your passion will help make your food shine. “It’s not as easy as it looks or sounds but if you believe in your cause it makes it easier,” explained the expert chef.

A word of caution from the canna chef is to make sure this is your calling, as the traditional culinary world is not welcoming cannabis – yet.

“Many look down on what I do, but I stand for my cause,” he said. “You must think about all the pros and cons before crossing that line.”

Chef Snyder tells Ganjapreneur that he’s in it for the right reasons, and wants to collaborate with other likeminded ganjapreneurs. In 2017, expect the Renegade Chef Co. to be breaking onto the scene in California, Colorado, and Massachusetts with an edible line coming to fruition soon after.